Barcelona, Spain (UroToday.com) At 2019 ASCO meeting, Davis and colleagues previously reported that treatment with enzalutamide rather than an older non-steroidal anti-androgen (bicalutamide, nilutamide, or flutamide), resulted in longer overall survival when added to standard first-line treatment, with or without concurrent early docetaxel, in mHSPC (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.86, p = 0.002).1 Additionally, enzalutamide also leads to longer progression free survival (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.33-0.49). At the ESMO 2019 prostate cancer session, Dr. Stockler and colleagues from the ENZAMET consortium reported results of the health-related quality of life data.

For ENZAMET, 1,125 men with mHSPC were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive testosterone suppression plus either enzalutamide or a non-steroidal anti-androgen. Randomization was stratified by volume of disease (high vs low, according to CHAARTED), planned early docetaxel, planned anti-resorptive therapy, comorbidity score (ACE-27), and study site. Health-related quality of life was measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30 and PR25 metrics at weeks 0, 4, 12, and then every 12 weeks until clinical progression. The authors used mixed models for repeated measures to calculate the least squares mean difference (LSMD), 95% CI, and p-value for comparisons of the randomly assigned groups for all assessments from weeks 4 to 156. For each analysis of deterioration-free survival, the endpoint was defined a-priori as the earliest of death, clinical progression, cessation of study treatment, or a 10-point worsening from baseline (minimum clinically important difference on scales scored from 0 to 100) in the pertinent health-related quality of life sub-scale: physical functioning, global health and quality of life, cognitive functioning, and fatigue.

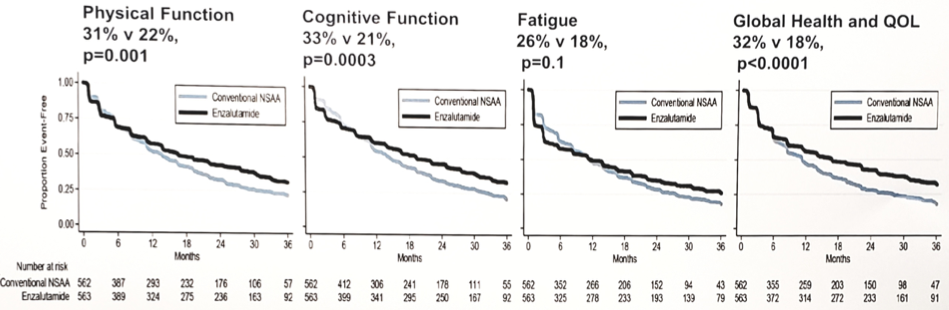

Completion of health-related quality of life forms in 1,016 men with a baseline assessment of health-related quality of life (among 1,125 men randomized) ranged from 94% at week 12 to 78% at week 156. Random assignment to enzalutamide vs non-steroidal anti-androgen was associated with modest impairments from week 4 to 156 in fatigue (LSMD 5.0, 95% CI 3.3 to 6.7, p < 0.0001), cognitive functioning (LSMD 3.9, 95% CI 2.4 to 5.4, p < 0.0001), and physical functioning (LSMD 2.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.8, p = 0.0002), but not for global health and quality of life (LSMD 1.1, 95% CI -0.4 to 2.6, p = 0.16). Deterioration-free survival rates at 3 years favored enzalutamide over non-steroidal anti-androgen for global health and quality of life (32% vs 18%, p < 0.0001), cognitive functioning (33% vs 21%, p = 0.0003), and physical functioning (31% vs 22%, p = 0.001), but not fatigue (26% v 18%, p = 0.1).

The effects of enzalutamide on health-related quality of life were relatively stable over time and unaffected by treatment with concurrent early docetaxel.

The authors concluded with the following summary points for their analysis of health-related quality of life in ENZAMET:

- The addition of enzalutamide maintained global health and quality of life

- Enzalutamide improved deterioration-free survival because early impairments in specific aspects of health-related quality of life were insufficient to outweigh the subsequent benefits of delayed clinical progression

- Enzalutamide is an appropriate option for men with mHSPC starting testosterone suppression alone

- For men who are candidates for docetaxel when starting testosterone suppression, longer follow up is needed to determine if the delays in progression and in time to deterioration with enzalutamide and concurrent early docetaxel also results in improved survival beyond three years

Clinical trial identification – ACTRN12614000110684, NCT02446405; EUCTR2014-003190-42-IE

Presented by: Martin R. Stockler, MBBS(Hons) MSc(Clin Epi) FRACP, Professor of Oncology and Clinical Epidemiology at The University of Sydney, a consultant medical oncologist at the Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Chris O’Brien Lifehouse RPA, and Oncology Co-Director at the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre.

Co-Authors: A. Martin 2, H. Dhillon 2, I. Davis 3, K. Chi 4, S. Chowdhury 5, L. Horvath 6, N. Lawrence 7, G. Marx 8, J. Mc Caffrey 9, R. Mcdermott 10, S. North 11, F. Parnis 12, D. Pook 13, M. Reaume 14, S. Sandhu 15, T. Tan 16, A. Thomson 17, R. Zielinski 18, C. Sweeney 19

2. University of Sydney, Sydney, AU

3. Monash University, Box Hill, AU

4. BC Cancer Agency – Vancouver, Vancouver, CA

5. Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospital NHS Trust, London, UK

6. Chris O’Brien Lifehouse RPA, Sydney, AU

7. Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, NZ

8. University of Sydney, Wahroonga, AU

9. Mater Misericordiae University Hospital University College Dublin, Dublin, IE

10. Adelaide and Meath Hospital, Tallaght, IE

11. University of Alberta, Edmonton, CA

12. Adelaide Cancer Centre, Adelaide, AU

13. Monash Health, Bentleigh, AU

14. The Ottawa Hospital Regional Cancer Centre, Ottawa, CA

15. Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, AU

16. Royal Adelaide Hospital RAH Cancer Centre, Adelaide, AU

17. Royal Cornwall Hospital, Truro, UK

18. Central West Cancer Services, Orange, AU

19. Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, US

Written by: Zachary Klaassen, MD, MSc – Assistant Professor of Urology, Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta University/Medical College of Georgia Twitter: @zklaassen_md at the 2019 European Society for Medical Oncology annual meeting, ESMO 2019 #ESMO19, 27 Sept – 1 Oct 2019 in Barcelona, Spain

Further Related Content: